Hometown Hero: Local recovery center battles addiction through culture

Published 1:30 am Friday, January 30, 2026

“There is no word for addiction in Somali,” Hussein Ugas told the Mirror. “How can we deal with a concept we don’t even have a word for?”

Ugas is the co-founder of Rahma Recovery, an organization that opened Washington state’s first accredited level two, culturally responsive sober living home for East Africans and Muslim men in November 2024.

Rahma Recovery provides “dignity, safety, and belonging to men in recovery” through their sober living house in Federal Way as well as through Narcan training and outreach to address substance use disorder and mental health stigma in their communities.

Ugas will soon be opening a women’s sober housing location as well, which will also be the first of its kind in the state.

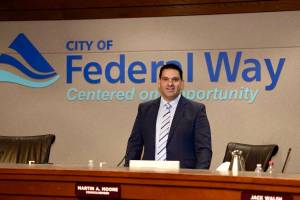

For his dedication to creating culturally-relevant support for those in recovery, and for working toward shifting a culture of shame and stigma around substance use, Hussein Ugas is the Federal Way Mirror’s Hometown Hero for the month of January.

About 13 years ago, Ugas was homeless on the streets of Minneapolis, Minnesota, struggling with addiction and PTSD that he had to address.

Last year, Ugas was a speaker at the 2025 King County’s Behavioral Health Legislative Forum and celebrated the one year anniversary of opening Salaam House.

The dream of Rahma Recovery began to form when Ugas started to notice the impact of his community’s stigma around drugs and alcohol on those that were struggling with addiction.

To combat this stigma, he shared his story with his community for the first time at a Somali Health Board event. After he spoke, he said a crowd of Somali mothers approached him who were desperately worried about their sons.

He felt called to do something to help, but didn’t know where to start.

One night, he got a phone call that two young people in the community had overdosed and another had died of gun violence. He stayed up all night praying, and in the morning, he called the Department of Drug and Alcohol Prevention for the state.

“I talked for two minutest straight, crying … asking them to help me to help my community,” Ugas said. “I was a truck driver without a high school diploma trying to open a methadone clinic.”

He was willing to do whatever it took to help his community, and ultimately settled on working to open up a sober housing location rather than a clinic.

Connecting with Washington Alliance for Quality Recovery Residences (WAQRR) helped him make that vision a reality and guided him through the steps to open a sober house and to apply for an initial grant to get him started.

At every turn, Ugas kept finding community members who were willing to help him make the project happen, especially those in the Muslim community of South King County.

Through these connections he was able to find someone with a house they had been renting for vacation rentals, fully furnished with eight beds, dishes and everything already ready to be made into a space for recovery.

Walking through the door of that house for the first time, Ugas said, was the moment he realized his life’s purpose.

Taking his nonprofit work full time meant nearly an 80% cut in pay, which was hard as someone who has fought so long to find stability. But Ugas said his happiness is now 110% of what it was before.

He still drives for Uber and Lyft on the side, among other things, in order to make it all work. He said it’s worth it when he gets to see the impact of the recovery program, community involvement, lifestyle changes and supportive environment that the residents of the Salaam House create together.

As part of their community work, Rahma Recovery partnered with organization Living Well Kent, which took over ownership of the Kent Farmers Market last year. They gave Salaam House a table at the market and the opportunity to grow produce on their land. At their booth, Salaam House volunteers educated the community on overdose awareness and taught almost 400 people how to use Narcan as they sold their produce.

Salaam House has so far had 25 men enter their program, and they’ve seen no overdoses and no complaints of any disruptive behavior from neighbors. Not every one of those 25 has been able to make it through the program or maintain sobriety. Ugas noted that even his own recovery journey was not linear and it can take time to truly leave addiction behind.

Outside of Salaam House, Ugas has also facilitated 15 family interventions, which led to 11 successful detoxes and admissions to treatment centers. He has also held 10 educational events at 10 different mosques to talk about recovery, as well as doing extensive community outreach.

Finding sobriety

Hussein Abdi, 31, is a graduate of Salaam House and told the Mirror it meant a lot to be able to go through his recovery process with those who shared his faith and culture. He started his recovery process last year and has been able to change his life through the house’s program.

In Islam, consuming alcohol is forbidden, and in the Somali community in general, “drugs and alcohol are taboo,” Abdi explained.

In American culture, alcohol and casual drug use is everywhere and it is such a big part of social life that it can be hard to resist. This is exactly what Abdi experienced when he left for college.

“While their home life, their culture and their religion forbids it, a lot of kids, especially in Somali culture, are very drawn to that lifestyle, and once they do get into that lifestyle, they don’t know how to speak to their parents and how to get the help they need,” Abdi said.

When Abdi got his first DUI, it’s for this reason that he didn’t tell his parents or anyone in his community.

Instead, his troubles kept getting worse, leading him to drop out of school halfway through his third year of college and face a challenging chapter of substance use and legal trouble as he missed court dates and probation check ins.

His family ultimately helped encourage him to consider connecting with Rahma Recover. Going to the Salaam House changed everything.

“I didn’t know, honestly, that there are programs out there that can really help you,” Abdi said.

He explained that the program helped him with his sobriety, with reconnecting with his faith and with dealing with the legal issues that had built up so that he could move forward with his life.

Although he said he would have learned many helpful things from other recovery programs, being able to spend time with others in his culture and who were also Muslim helped him in ways other programs couldn’t have.

“I would have been a lot different from the person I am right now, the things that I understand about my inner self,” Abdi said. “I wouldn’t understand how people like myself can get control of our lives and become better men and better people.”

Ugas in particular has been a big inspiration to Abdi.

“For me, you don’t meet a lot of people who you can see as role models, that also went through what you went through,” Abdi said. “I can see myself being somebody that can get my life turned around, be part of the community and do things that help other people while also helping myself.”

Through Rahma Recovery, Abdi was connected with an outpatient treatment program in Federal Way called Intercept Associates, which he said has also been instrumental in this new chapter of his life.